Reed, Alan (Pallas) (July 2002)

Added: July 28th 2002A Pallas, As Seen Through The Reed - Or: Pallas, As Seen Through Alan Reed

Pallas is one strange cookie. After all, there aren't that many bands that take thirteen years to make a comeback album and then release a live record and yet another studio effort in a relatively short time. Fact is stranger than fiction, however, and with its latest, The Cross & The Crucible, this Scottish act is dead on target on its quest to reclaim a long-forlorn fanbase and to revive what at one point was really nothing but a group of musicians trying to get it together once again. Lineup changes, record label conflicts, lucky coincidences, and a desire to keep going have kept the Pallas history alive for more than two decades now, and yours truly recently got the chance to interview vocalist Alan Reed and get some answers, including one related to Pallas' early attempts at being a boy band!

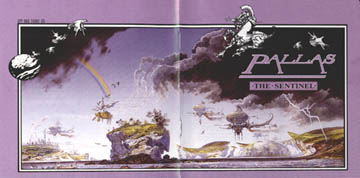

Marcelo Silveyra: When you joined Pallas after the dismissal of Euan Lowson in 1985, getting the job was probably kind of intense. Not only because you'd been a fan of the band previously, but also because Lowson had built up a massive live reputation by performing stunts such as coughing up blood on "Crown Of Thorns" and slitting his wrists on "The Ripper." Did you at any moment feel intimidated by Lowson's reputation and the expectation that both the band and its fans would have of you? Do you think the fact that the band had only released Arrive Alive and The Sentinel by the time you joined helped you win over the fans more quickly?

Alan Reed: It wasn't the easiest of situations to go through ... I'd been a fan of the band for some time and was well aware of how strong a stage presence Euan was, and I knew I wouldn't be comfortable trying to do that theatrical thing. However, I also felt strongly that what was lacking from Pallas on stage was a proper focus. Fascinating though Euan's approach was, I felt it kind of detracted from the impact of the band's music. On-stage he was kind of divorced from what went on - he only made occasional grand appearances and didn't communicate directly with the audience much. In fact, the first time I saw Pallas he didn't appear until well into the set ... I actually thought Graeme [Murray, the band's bassist] was the vocalist until then! I felt strongly I could add the missing ingredient to the band - which was odd, because up till that point I really considered myself to be a bass player. I didn't really have plans to become a vocalist/frontman. I really wouldn't have considered joining any other band in that capacity - it just felt right!

In terms of how the fans dealt with my arrival, there were obviously some who couldn't accept Euan was no longer involved... It was particularly difficult in the band's hometown of Aberdeen, where Euan was still very much in evidence. The general response was pretty positive however. I was very sensitive to what people thought, but quickly got the feeling that I was generally being accepted. I think it helped that I didn't try to emulate him in any way. He did what he did, and it was pointless to try to match it on the same terms. I don't think that the band's releases so far gave me any sort of advantage or disadvantage. In the UK the band was already fairly well known. I think it was slightly easier in mainland Europe, because they had no experience of early Pallas gigs to compare... I was just the singer in the band when we first went there.

MS: Something that struck me as peculiar once was seeing Pallas included on the Heavy Metal Heroes compilation along with New Wave of British Heavy Metal acts such as Witchfinder General. Not actually because Pallas isn't really a heavy metal band, but more because of the disturbing similarity in how both the British metal and progressive rock revival movements fizzled out only after a few years, with only a couple of their members making it to the big leagues. What was it like to see an enormous level of excitement around such musical activity in Great Britain, only to have it fall as quickly as it had risen?

AR: Well, our inclusion on that sampler wasn't as strange as you think. Pallas were seen as very much at the heavy rock end of things - particularly live. There were as many comparisons to Rush as to Genesis at that time, and the audience we had was much more of a mainstream rock one than the one drawn to the likes of IQ, Pendragon, etc. etc ... The one thing we had in common with Marillion was an appeal to a crossover audience. The "new wave of prog" thing was very much an invention of the London-based media ... we only came across these other bands (with the exception of the Marillos) when we came down to play the Marquee ... to be honest, most of them were only playing in London and their home areas, while we were already gigging across the whole of the UK on the standard rock circuit. It never seemed likely to me that there was likely to be a mass movement of bands into the big leagues ... most were only really starting to develop, and still needed to cultivate a wider fanbase. When I first saw Pallas, what came across was a band that was likely to make it to the big time on the basis of its ability and individuality. I only became aware of the "prog" thing later...

MS: A curious thing about the band having recorded The Sentinel was that, in order to be able to record with Eddie Offord, Graeme had to sell his Porsche in order to cover the expenses of recording in Atlanta. An obvious conclusion was that the band was extremely excited with the future at that point. When you joined Pallas, was this excitement still around or was there a bit more wariness regarding decisions? Were there any signs at that time of the problems with EMI that were just around the corner?

AR: There was still a lot of excitement, but it was tinged with lessons from the school of hard knocks. Obviously losing a vocalist is a traumatic experience for a band; particularly at such a sensitive stage in their recording career. EMI were also going through major problems at the time ... The day after my first gig at the Marquee, they cut the roster in half - we were lucky not to be dropped. EMI became increasingly difficult to deal with. The uncertainty at the company meant that we kept being given different people to deal with, and it was almost like we were constantly having to re-prove ourselves to them again and again. You didn't feel you could trust them to act in your best interests ... you weren't sure that they understood or believed in the band - all those people that had either left or moved on... but they were still writing the cheques!

MS: Some time after you had joined Pallas, you recorded The Knightmoves EP. Was the sole purpose of that to introduce you to the Pallas fanbase and prove that you were the right man for the job? How did it feel for you to move from live playing to actually recording with the band at that point?

AR: Actually, recording came first ... we'd demoed several numbers and had been writing together for a couple of months before I performed live with the band. The Knightmoves [release] was intended to serve several purposes. It would take time to write a completely new album, and it had already been some time since The Sentinel due to the delays of finding a new singer. Obviously it was also an opportunity to give a flavour of how the band sounded with me singing. Most importantly, it was also intended to act as a musical bridge to the new album. We already intended to do something different - it wasn't really sensible to go for another full-blown concept album - so we decided to introduce the idea of change in this intermediate form. We wanted to show that we were still in touch with what went before, but were about to develop somewhat. The title came from the words to another track, "...the Knight (Sentinel) Moves On."

MS: Then came the innovative The Wedge, in which you tried to break with several barriers of progressive rock and crossed over all sorts of borders. How important was producer Mick Glossop in the creation of this experimental mood, and why not use Eddie Offord once again? Since all the time that the experimentation took caused you to finish up the album in a sort of hurry, was there anything you wished you'd done differently after the album was released?

AR: The band didn't use Eddie again because basically they felt he'd let them down. They'd been very happy working with him, but he'd been left to mix The Sentinel on his own after time ran out and the band had to come back from Atlanta. When they finally got the mix, it was nothing like they'd expected ... it had squeezed out all the life ... the guitars and drums were way too low. Basically, Eddie had got into another project and did a quick mix which the guys were never happy with. It wasn't the album they thought they'd recorded...

Mick was one of several guys that EMI suggested ... he was the only one who seemed to have a real handle on what we were trying to do, which was "progress" (i.e. develop). We worked with him on the Knightmoves [EP], and it wasn't easy, but he made us question every preconception that we had about music ... he wouldn't let us use certain musical clichés, and had us focus on song and arrangement rather than intricate parts. He really got us to take everything apart and then put it all back together after exhaustively trying all kinds of alternatives. When it came to The Wedge, Mick was involved at an early stage; coming up to the farm studio and making us re-think all the material we'd written before we even got to make our routine for the album. He made us listen to all kinds of stuff we'd never have thought of listening to, to make us think past Mellotrons and Mini-moogs. He brought us a Linn-drum to play with so we could start thinking about the possibilities of drum machines and sequencers. I think in some ways we were basically trying to do a heavy rock version of [Peter] Gabriel 4, with some of the mass appeal of 90125. It was a hard task we set ourselves. The album was really cutting edge at the time - especially for a traditional rock band. We had to learn a lot of new technology, most of which was still in its infancy and took a lot of effort to get to work properly. Unsurprisingly we ran out of studio time (twice in fact), but EMI were happy enough to give us the extra budget to finish it. It was close though ... and we knew the finished result would upset some of the traditionalists.

I suppose in retrospect we were fighting on too many fronts at once ... proving to the critics that there was more to us than a taste for seventies prog albums, proving to the audience that rock music could include samplers and sequencers, proving to the record company that we could be an album band and still be commercial enough for them to understand. If there's one regret I have it's that we didn't go far enough in any one direction. Perhaps we should have abandoned trying to write a single and concentrated on making a definitive album, but that's not how the business operated at that time, and we were caught up in all the pressures that went with having a major deal.

MS: After The Wedge was out, you walked out of your contract with EMI, as you weren't happy with the support (or lack thereof) they'd given you. Recordings for a new album, Voices In The Dark, ensued, but the record was never actually released because you always seemed to be on the verge of a new record deal when things fell through. What was Voices In The Dark like? Did you ever consider releasing the record independently back then?

AR: Voices In The Dark was a refinement of what we'd learnt through The Wedge. It was rockier and had more identifiably "prog" elements, I suppose ... basically it was a more confident balance. We came close to a new major deal on a couple of occasions, and one in particular only failed to happen because of a bizarre coincidence involving a senior EMI executive joining the new company. We did start to record stuff for a label our management had set up, and Mick Glossop was in the frame to produce, but essentially the money ran out and we had to find other ways of making a living.

MS: You left Pallas in 1988; the same year that you graduated from university with a degree in English literature. Coincidence?

AR: The two are psychologically related. I'd completed the last two years of my degree while being on the road with Pallas during our most difficult times (I'd previously put my degree on hold when I'd joined, but later decided to try and fit it around Pallas). I guess we reached our lowest ebb around the time I graduated ... I suppose I figured it was time to do something new. It wasn't an easy decision to take. It took the best part of five years before I was ready to get involved in music again.

MS: Next year, Pallas released Sketches, a compilation of rough demos that kept the band name alive in a way, but which was released when Pallas didn't really have a new album to present to the public. Since you had left the fold the year before, what was the status of the band at that point? What were your thoughts on the release of Sketches at the time?

AR: To tell the truth I was a bit annoyed, because they hadn't even asked me. I was strongly involved in writing quite a lot of it, so I felt a bit aggrieved. The others were still trying to get something going and were even trying out other singers, but it didn't really gel. Mike Stobbie (who'd replaced Ronnie [Brown] on keyboards) was living in London, so we kept in touch and he let me know what they were up to, but the magic didn't seem to be there.

MS: Then came the reissue of the Pallas albums in 1992 and the release of the "War of Words" and "Never Too Late" demos, as well a considerable enthusiasm on behalf of the band regarding the immediate future. There was even a lineup change with Mike Stobbie replacing Ronnie Brown on keyboards. What happened then? And why would Graeme and

Niall (Mathewson, the band's guitarist) start working with Ronnie again a few years later instead of with Stobbie? [Ironically, Stobbie had formed part of Pallas before but left in 1979, thus never recording anything with the band]

AR: Mike actually joined in '87, when Ronnie left for personal reasons. He'd recorded some of the stuff on Sketches and the early Voices sessions, which we later abandoned. What happened was that Graeme managed to lease back the EMI stuff for CD release and that stimulated interest in the band, which gave everyone a fresh enthusiasm. I'd been asked if I was interested in rejoining and the wounds had healed enough to give it a go. We started writing and demoing - Mike and I in London, Graeme and Niall in Aberdeen (occasionally all getting together to pool our ideas). We demoed about 3 albums worth of stuff, but it never quite came together in the way that made all of us happy. Gradually it looked as if it would never happen.

What happened with Ronnie was that Graeme bumped into him while out shopping. Things had ground to a halt, with Mike and I being in London, and Mike in particular being increasingly busy with other projects. Graeme and Niall felt they needed a keyboard player to help them get some of their ideas down and asked Ronnie if he'd help out - no strings attached. Initially Ronnie had no intention of rejoining the band, but they rediscovered how well they worked together and gradually it became clear he should play a larger role. Mike's still pretty much part of the family, but it was easier all round that he stepped down.

MS: You decided to give it one last shot in 1997, after Graeme had called you and said that there were some really exciting things going on in the Pallas camp. The result would eventually be Beat The Drum, the first Pallas album in thirteen long years. Now, a few years later, how glad are you that you made the decision to try things one last time?

AR: We're PALLAS again. It's fulfilling in the way that it was to begin with. We're creatively and personally happy working together, without any of the bad shit we've had looking over our shoulders in the past. Pallas always has been like being part of a family, and now it's one where we feel we're doing the right thing at the right time and it's all going our way. It's a genuinely satisfying feeling. It was always great being part of this band ... now it feels that the rest of the world has finally come around to our way of thinking.

MS: Ok, now we're going to move away from Pallas territory for a second in order to head into our trademark series of oddball questions, of which you'll probably get the hang of fairly quickly. Alright, hypothetically speaking, what would happen to Colin Fraser (drums) if he suddenly decided to play a twenty-minute long drum solo in the middle of one of your concerts?

AR: Isn't that what he usually does? We normally just play all over it so people don't notice too much. Well, for starters, the rest of us would probably go for a meal and a couple of pints and leave him to it. Once we'd come back, I suppose we'd let the audience decide what was a fit and proper punishment ... maybe make him play "Arrive Alive" over and over again (he's not to keen on it!).

MS: Did Graeme ever try to steal your Shergold twin neck bass? If so, did you hit him with it and tell him not to try doing that ever again?

AR: Graeme "borrowed" my Shergold twin neck in August 1984, about two minutes after it arrived in Aberdeen - and I'm still waiting for it back. But he's made such a mess of it I'm not sure I want it now.

MS: If your acoustic guitar playing on "Who's To Blame" hadn't been included on The Cross & The Crucible, how long would it have taken for the studio to catch on fire with the remaining members of Pallas inside it?

AR: Well, I'm not altogether convinced Niall didn't just rerecord it once I'd gone back to London, but they're letting me play electric guitar on stage now (sadly that cheap Fender shit - I'm a Gibson man really), so I'll let them off. Besides, I need the rest of them to fill in the gaps between the singing and the acoustic guitar parts [smiles].

MS: What's a cooler band name: Rainbow or Pallas? [Pallas once had the name Rainbow, before Ritchie Blackmore formed a band under the same moniker] Elaborate.

AR: Well they both have a scary guitarist in ... but one recorded "Kill The King," so I'd have to go with them.

MS: You're in a cave with only two exits. One is guarded by a sentinel that only tells the truth, the other one by a sentinel that only lies. Furthermore, one of the doors will lead you to a permanent and unavoidable part in the Backstreet Boys, the other one to your normal life. You may ask only one question to figure out which door is which. What would you ask?

AR: Which door do I go through to join the Backstreet Boys? (Actually, we always wanted to be a boy band, but in the eighties it made more commercial sense to sell out as a prog rock outfit)

MS: Ok, now returning to more normal questions ... by the time you released Beat The Drum, Colin Fraser had replaced Derek Forman in the drummer position. Did the change have anything to do with Derek not being able to make the gig in Holland for which you pressed the Day Of Dreams demo?

AR: Yes...

MS: What comes across as particularly curious is the fact that you released the live Live Our Lives shortly after Beat The Drum had been released. And while it is true that there hadn't been an official live album ever since Arrive Alive, it also seemed to be quite a quick release after only a short time of coming back. Was this a way for Pallas to state that Beat The Drum was not only a flash in the pan, or just a gift for the fans?

AR: Both really ... we wanted to show we were genuinely active and weren't going to just disappear again. We also knew that we'd have to stop playing some of the old stuff at some point to let new stuff into the set. We'd only intended to do the "Atlantis" suite on those dates, so if we hadn't recorded it it'd have been lost forever. We figured people would want to have a recording of it (we did).

MS: Now, regarding your latest album, The Cross & The Crucible, this one seems to be musically moving ahead more than its predecessor, which was more like a cross between all the previous characteristics of Pallas (i.e. The Sentinel and The Wedge). With only a few official full albums to the band's credit, how important is it for you to keep forging ahead with the Pallas sound?

AR: You die if you don't keep moving ... it would get pretty boring pretty quickly if we just kept repeating ourselves! My favourite band was and still is Rush - they've always been my touchstone for a band that keeps the essence of itself intact, but keeps fresh by developing. I like to think that Pallas aims for the same things. With Cross, I think we've finally crystallised on record how Pallas sounds in our heads. The challenge now is to move on from that without losing the plot, either re-treading old ground or losing the essence of what makes us us.

MS: The Cross & The Crucible is an ambitious effort lyrically, with the concept of it basically trying to tackle the entire history of mankind and the human essence lying behind it. I once read that Graeme and you have some disagreements when discussing what should be represented in the band's lyrics, so how does that affect them? Have you ever had a discussion that ended in a stalemate and thus was not included in the album? Furthermore, how much did your work in the BBC influence the political and religious concepts running behind The Cross & The Crucible?

AR: Graeme and I used to argue about most things ... not so much now. The lyrics for The Cross are about 50/50 him and me. It tends to be more about emphasis than anything. Graeme likes to lock into a concrete image or metaphor, whereas I like to be a bit more vague and let the words suggest further associations for the listener. We're both pretty critical of each other, but we find it works for us. I used to be very precious about it in the early days, thinking that as the singer I should be responsible for all the words, but one of the things I learned from Mick Glossop was that the important thing is that the final product is the best it can be - and that means listening to other people's ideas. I guess I just felt inadequate without a guitar round my neck (guitar-envy) [smiles]. I can't remember us ever getting into a stalemate over a lyric to the point it didn't get used, but we often go through about 15 versions until we get to the one we use - and that often changes as we're recording it, when we discover the sound of the words isn't right (it has to work musically as well, y'know).

As for my being in the BBC, well obviously everything you do and are exposed to affects what you write about. I've got some strong views about some of the things I've seen which obviously I'm not allowed to voice in my job. I suppose that informs much of what we've written about in Cross. "Who's To Blame?" is probably the most obvious, taking the Balkans conflict as a starting point for all the stupid battles that go on between peoples, while the rest of the world stands idly by. The title actually came from an argument with Graeme, where he was having a go at the role of the media saying (with some justification) that all we do is look for scapegoats. "All you guys do is say 'Who's to blame...who's to blame?'" So I wrote a song called "Who's To Blame?" But the question has a wider resonance - especially after Sept 11th.

MS: Looking at the history and results of Pallas, something comes across as rather interesting. Now all of you have families and jobs, something that keeps you from being able to rehearse whenever you want to and from organizing large-scale touring. Yet a lot of bands that were very successful during their careers don't seem to have this advantage, as promotion and touring take up a lot of their private time. Looking back, is it actually a good thing that the problems that Pallas went through eventually meant that you would all be able to live "normal" lives and yet be able to play in a band, release music you want to, and do the occasional live concert for your fans?

AR: I think we're much saner and happier individuals as a result. I can't imagine things being any other way now, and at least we know that we're together because of our love for the music we make together, rather than purely to make money. When I look at some of our contemporaries who tasted greater success, but who are now struggling to maintain a career, I know who I'd rather be. We went through a lot of pain, but it's nothing to what they're going through. We managed to recover and become stronger individuals as a consequence. For us, being musicians is an end in itself and "the business" can't suck that pleasure away from us as it threatened to do in the past. But we also know that there's more to life than playing in a rock band, and that we could live without it if we had to

In 2010, Reed's association with Pallas ended. In May 2011, Reed released his solo single " Begin Again"- ed.

Discography:

Pallas - The Knightmoves EP (1985)

Pallas - The Wedge (1986/2000)

Pallas - Knightmoves To Wedge (combo reissue)

Pallas - Beat The Drum (1999)

Pallas - Live Our Lives (2000)

Pallas - The Cross And The Crucible (2001)

Pallas - Mythopoeia (2002)

Pallas - Blinding Darkness (2003)

Pallas - The Dreams Of Men (2005)

Pallas - The River Sessions 1 (2005)

Pallas - The River Sessions 2 (2005)

Pallas - Live From London 1985 (2005)

Pallas - Official Bootleg 27/01/06 (2006)

Pallas - Moment to Moment (2008)

Alan Reed - Dancing With Ghosts (2011)

Alan Reed - First In A Field Of One (2012)

Alan Reed - Live In Liverpool (2013)

Pallas - Blinding Darkness (DVD) (2003)

Pallas - Live From London (DVD) (2008)

Pallas - Moment To Moment (DVD) (2008)

Interviewer: Marcelo Silveyra

Artist website: reddwarfrecordings.co.uk

Hits: 3437

Language: english

[ Back to Interviews Index | Post Comment ]